Adaptive Capacity: An evolutionary-neuroscience model linking exercise, cognition, and brain health Adaptive Capacity: An evolutionary-neuroscience model linking exercise, cognition, and brain health NEUROPLASTICITY An overview of the current scientific understanding of neuroplasticity and the brain, (Costandi, 2016):

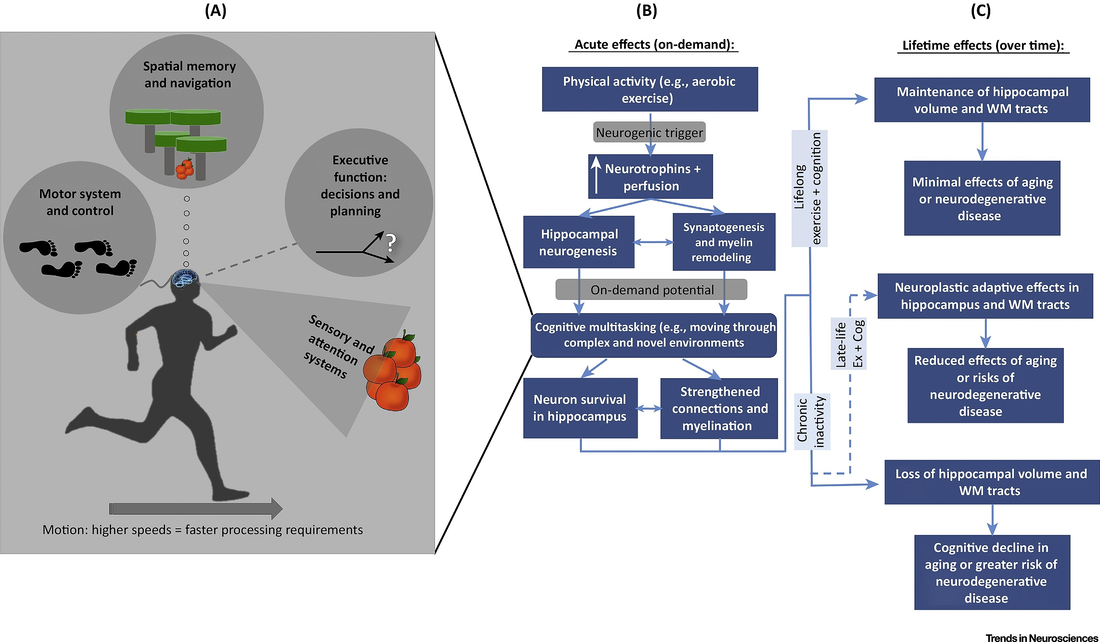

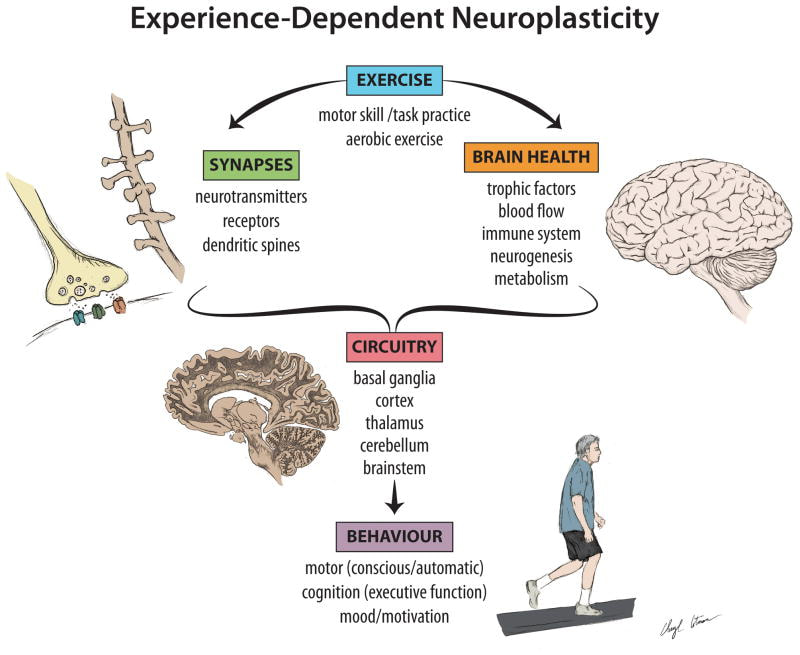

A brief overview of the historical discovery of neuroplasticity The discovery of neuroplasticity extends back approximately 200 years. In the 1780’s Swiss naturalist, Charles Bonnet, and Italian anatomist, Michele Vincenzo Malacarne, corresponded about the brain's ability to grow and change from practicing “mental exercise”. Then in 1791 German physician, Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring, published a textbook titled “Does use and exertion of mental power gradually change the material structure of the brain.” He pondered that in the same way we used our muscles to become stronger the possibly existed that the same could happen within the brain. In the 1890’s Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal whose advancements in microscopy and (cell) staining methods propelled examination of nervous tissues that led to the discovery of cells called neurons. And the list goes on and on, (Costandi, 2016). From the beginning, advancements in neuroscience have and continue to be a multidisciplinary effort. In 1969 Paul Bach-y-Rita published an article in a European science journal citing his research using a machine that sent signals to the damaged area of a brain that ultimately cured retinal damage in some cases. Bach-y-Rita’s research demonstrated that our brains were capable of neuroplasticity and using other area’s to restructure and create new neural growth. The research publication and its avant-garde nature caused isolation from some of his peers. Bach-y-Rita had a multi-disciplinary background and approach and tended to follow ideas as they evolved. As a neuroscientist, he had expertise in medicine, psychopharmacology, ocular neurophysiology, visual neurophysiology, and bio-medical engineering. Doidge (2007) asserts that Paul Bach-y-Rita stated “we see with our brains” and that if one area is damaged, another area can take over. He referred to this process as “sensory substitution”. It was Eric Kandel who “was the first to show that as we learn, our individual neurons alter their structure and strengthen the synaptic connections between them…” Doidge (2007) explained that Kandel’s work demonstrated that learning produces new neurons in the brain that influence our genes and that psychotherapy changes people’s brain structure, “it presumably does so through learning, by producing changes in gene expression that alter the anatomical pattern of interconnections between nerve cells”. Neuroplasticity and the CNS Neuroplasticity is the ability of the central nervous system (CNS) to adapt to environmental changes and experiences and to adapt to injury or disease. This plasticity ability in the CNS allows modifications to successfully cope with new circumstances, allow for recruitment of new neural networks, and creates neural changes in areas of the brain, (Sharma, N., Classen, J., & Cohen, L. G., 2013). Mechanisms of plasticity and metaplasticity (activity-dependent changes in neural functions that modulate subsequent synaptic-plasticity such as long-term potentiation “LTP” and long-term depression “LTD”) are important for learning and memory, and in functional recovery from lesions in the CNS, and stroke. Plasticity changes occur at the cortical levels and reorganize subcortical structures. “…neural substrates of recovery of function are likely distributed over multiple sites at different levels of the neuroaxis and not restricted to one specific location…”, (Sharma, N., Classen, J., & Cohen, L. G., 2013). It is recent that our understanding neuroplasticity can occur in the adult CNS and in elderly people. This mechanism includes the recruitment of multiple brain regions in the elderly and in stroke recovery patients. Neuroplasticity occurs when the nervous system responds to experiences, thus experience-dependent. Experiences create a stimulus that ignites neural firing patterns in the brain to imprint or to re-transcribe an experience, or to reorganize the infrastructure of previous experiences via new neural pathways. Researchers Cramer, Sur, Dobkin, O'Brien, Sanger, Trojanowski, & Vinogradov (2011) examine the function of neuroplasticity in the context of clinical psychology via interventions and treatments, including CNS trauma recovery. “To advance the translation of Neuroplasticity research towards clinical applications, the National Institutes of Health Blueprint for Neuroscience Research sponsored a workshop in 2009. Basic and clinical researchers in disciplines from central nervous system injury/stroke, mental/addictive disorders, pediatric/developmental disorders, and neurodegenerative/ aging identified cardinal examples of Neuroplasticity, underlying mechanisms, therapeutic implications and common denominators”, (p. 1592, 2011). Experience-dependent clinical interventions based on the principles of neuroplasticity require a multimodal treatment approach. Implementing the Hebbian principles, a neuroscience theory explaining the process of neurogenesis during learning, with cognitive behavioral techniques, achieving tasks and goals, socializing and exercising, can produce a measurable outcome. “A key principle in neuroplasticity is the value of coupling a plasticity-promoting intervention with behavioral reinforcement…” (Cramer, Sur, Dobkin, O'Brien, Sanger, Trojanowski, & Vinogradov, p. 1598, 2011). Participating in regular physical exercise and learning something new illuminate the experience-dependent neural growth aspect of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis. “Aerobic exercise is associated with increased neurogenesis and angiogenesis…”, “…aerobic exercise programs lasting even just a few months significantly benefit cognitive functioning…have been shown to increase brain volume in a variety of regions (Colcombe et al., 2006; Pajonk et al., 2010)…and to enhance brain network functioning…” (p. 1600, 2011). Exercise enhances cognitive functioning which increases our learning capacity. Interventions and treatments designed with the intention of working with the principles of neuroplasticity are used for various CNS injuries, like traumatic brain injury. These treatment interventions are measurable in terms of outcome. “Interestingly, after spinal cord injury, treatment-induced brain plasticity can be measured in the absence of behavioral change”, (p. 1594). The mechanisms of neuroplasticity apply to a range of CNS injuries and treatments. “Studies of motor recovery after stroke illustrate the principle that many forms of neuroplasticity can be ongoing in parallel. Injury to a region of the motor network can result in spontaneous intra-hemispheric changes, such as in representational maps, e.g. the hand area can shift dorsally to invade the shoulder region (Nudo et al., 1996; Muellbacher et al., 2002) or face region (Weiller et al., 1993; Cramer and Crafton, 2006)”, , (Sur, Dobkin, O'Brien, Sanger, Trojanowski, & Vinogradov, p. 1592-3, 2011). A rehabilitative perspective includes patients who’ve suffered CNS injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury. In particular, patients recovering from stroke are dependent upon new neural growth, neurogenesis, and new neural patterns and pathways, neuroplasticity. The brain of a recovering stroke victim begins reorganizing itself. EPIGENETICS fundamentals (“what-is-epigenetics”, 2018). Epigenetics is a (complex) biological mechanism that switches genes off and on. The process of epigenetics affects how genes are read by certain cells.

In general terms, it’s understood that our genetic inheritance plays a key role in either our ability to have a long healthy life or for developing a chronic disease and illness. Epigenetics is a recent scientific discovery to the study of genetics. Epigenetics shows us that behavioral and environmental lifestyle choices may influence up to 50% of our genetically inherited predisposition. Both endogenous (growing from within an organism) and exogenous (growing from outside an organism) epigenetic influences can determine how our genes are expressed. “A recent addition to genetics has been epigenetics, which includes the role of the environment, both social and natural, including day-to-day habits, lifestyle and personal experiences on human health. Epigenetics establishes a scientific basis for how external factors and the environment can shape an individual both physically and mentally”, (Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B., 2014). Epigenetics refers to how our inherited genes are used or expressed. Behavioral and lifestyle choices affect which genes are switched on, or “expressed”, and which genes are switched off, or “silenced”. During the course of our lives, depending on environmental factors we are exposed to, epigenetics is capable of either positive or negative changes to our gene expression. (Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B. (2014). EPIGENOME The epigenome integrates all the molecular and chemical cues from the cells and from the environment. It represents the ability of the genetic organism to adapt and evolve in response to environmental stimuli. It is therefore dynamic and flexible. “Ultimately, the environment presents these various factors to the individual that influence the epigenome, and the unique epigenetic and genetic profile of each individual also modulates the specific response to these factors”, (Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B. (2014). Epigenome biology A genome “marker” is the epigenomic compound that attached to (our) DNA with instructions, we inherited this as it was passed down generationally, (https://www.genome.gov/27532724/epigenomicsfact-sheet/). While “genome” refers to the whole DNA sequence and the “epigenome” refers to the entire pattern of epigenetic modifications across all genes, including methylation DNA tags. “The epigenome is a multitude of chemical compounds that can tell the genome what to do. The human genome is the complete assembly of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid)-about 3 billion base pairs - that makes each individual unique. ... Rather, they change the way cells use the DNA's instructions”, which means they can be influenced to either turn on or off. Exercise effects epigenome How we may influence our gene expression, switching genes off and on, this mechanism can be harnessed via exercise. “Exercise is a non-pharmacological life-style factor, which plays an important role in maintaining a healthy brain through out life and in human ageing. It is a powerful environmental intervention capable of gene expression change, improved neurogenesis, enhanced synaptic plasticity and signaling pathways, and involving epigenetic regulation in the brain and cerebellum in humans, Raji et al. 2016...", (Rea, I. M. (2017). Exercise can be considered a preventative medicine. It can reduce the risk of developing a chronic illness and enhance one's overall well-being. Scientific research has identified some molecular pathways that show how physical exercise produces changes in the human epigenome. This finding indicates the potential for cognitive enhancement, improved psychological health, better muscular fitness, and extends to overall better aging and improved quality of life throughout one's lifespan. “Exercise is a key factor in maintaining our functional autonomy and can protect us from sarcopenic loss of muscle mass and strength which occurs with increasing age, and which is a major contributor to the frailty syndrome, Walston 2012; Cruz-Jentoft et al. 2010; Morley et al. 2001”, (Rea, I. M., 2017). Exercise activates certain genes by adding tags to DNA via methylation. These tags turn on or off gene switches. A regular exercise routine can cause a “modification in the genome-wide methylation pattern of DNA…”. Even a single exercise event causes immediate changes in the methylation pattern of certain genes in our DNA, and thus affects gene expression, (Rea, I. M., 2017). EXERCISE- EPIGENOME-EPIGENETICS Making healthy lifestyle choices like regular exercise is a way each person can actively modify their epigenome, and thus their epigenetics, in an effort to preserve and prolong their lifespan. Exercise activates epigenetic tags added to our DNA, such as methylation, which allows our DNA to better regulate metabolism and create beneficial changes to the skeletal muscle. “The health benefits of physical exercise, especially on a long term and strenuous basis, has a positive effect on epigenetic mechanisms and ultimately may reduce incidence and severity of disease, Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2012”, Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B. (2014). Exercise activates a cellular stress response. Aerobic and anaerobic exercise re-energizes the mitochondria. Our muscle growth during a lifespan is regulated by anabolic, the chemical reactions that synthesize molecules in metabolism, and catabolic, the destructive metabolism and breaking down of more complex substances with the release of energy, mechanisms of our gene expressions. Exercise revitalizes the mitochondrial function in our muscles. “It not only improves muscle function but also quality of life, with exercise improving mitochondrial function in older individuals as much as in younger exercising individuals. “Enzymatic activity in response to the environment promotes addition or removal of epigenetic tags on DNA and/or chromatin, sparking a cavalcade of changes that affect cellular memory transiently, permanently or with a heritable alteration”, (Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B., 2014). While the research referenced in this article focuses on exercise as a way to influence of epigenetics (gene expression), this concept can be applied to many other activities like learning new things, exposure to novel challenges and engaging in new tasks. Additionally, these research includes epigenetics in response to addiction and unhealthy lifestyle activities. I've chosen to focus my article on exercise and healthy lifestyle benefits. Express your gene's wisely! References

Copyright © Lisa Lukianoff, Psy.D., 201

Organizational cognitive neuroscience (OCN) is a new term used to describe the intersection, integration and application of neuroscientific discoveries with organizational and consulting psychology.

OCN is being defined in business leadership and marketing research. "…taking a wider neuroscientific approach to researching marketing or business-relevant problems and decisions will allow a greater understanding of why in general we behave or react the way we do, and a correspondingly greater ability to predict this”, (Lee, N., Butler, M., & Senior, C., 2010, p. 130). Organizational cognitive neuroscience (OCN) is an interdisciplinary study incorporating social psychology, organizational psychology and neuroscience. Neuroimaging and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies allow us to measure brain activity. It does so by showing the changes of blood flow associated with neural activity, (Butler, M. J.R., O'Broin, H. L.R., Lee, N. and Senior, C., 2016). This brain imaging technology has allowed scientists to map activity within regions of the brain to examine human behaviors and responses. These discoveries are expanding organizational psychology towards more neurobiological based interventions and assessments. “The organizational cognitive neuroscience approach … is not concerned with only the application of neuroscience methodologies to organizational research questions. Instead, the term ‘organizational cognitive neuroscience’ designates a genuinely multidisciplinary approach, in terms of both theory and method … organizational cognitive neuroscience is not simply the study of brain systems themselves but may also incorporate the use of prior knowledge of brain systems to develop new hypotheses about organizationally relevant issues…”, (Butler, M. J.R., O'Broin, H. L.R., Lee, N. and Senior, C., 2016). We now have a greater understanding and insight into the process of emotional arousal and response patterns for individuals. Brain science imaging techniques are able to teach us and show us the neurological process of decision-making. “By combining this approach with functional brain scanning it is possible to understand which areas of the brain generated that specific emotional response—and whether distinct brain regions are involved in other types of decision making”, (Lee, N., Butler, M., & Senior, C., 2010, p. 130). Organizational cognitive neuroscience (OCN), while still in its infancy, is quickly forging a new way of thinking about human behavior and decision making from a neurobiological brain systems approach. References Lee, N., Butler, M., & Senior, C. (2010). The brain in business: neuromarketing and organizational cognitive neuroscience. Journal of Marketing. Volume 49; pp. 129–131. doi: 10.1007/s12642-010-0033-8 Butler, M. J.R., O'Broin, H. L.R., Lee, N. and Senior, C. (2016). How Organizational Cognitive Neuroscience Can Deepen Understanding of Managerial Decision-making: A Review of the Recent Literature and Future Directions. International Journal of Management Reviews. Volume 18; pp. 542–559. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12071 An overview:

“Exercise is a non-pharmacological life-style factor, which plays an important role in maintaining a healthy brain through out life and in human ageing. It is a powerful environmental intervention capable of gene expression change, improved neurogenesis, enhanced synaptic plasticity and signaling pathways, and involving epigenetic regulation in the brain and cerebellum in humans, Raji et al. 2016...", (Rea, I. M. (2017). EPIGENETICS In general terms, it’s understood that our genetic inheritance plays a key role in either our ability to have a long healthy life or for developing a chronic disease and illness. Epigenetics is a recent scientific discovery to the study of genetics. Epigenetics shows us that behavioral and environmental lifestyle choices may influence up to 50% of our genetically inherited predisposition. Both endogenous and exogenous epigenetic influences can determine how our genes are expressed. “A recent addition to genetics has been epigenetics, which includes the role of the environment, both social and natural, including day-to-day habits, lifestyle and personal experiences on human health. Epigenetics establishes a scientific basis for how external factors and the environment can shape an individual both physically and mentally”, (Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B., 2014). Epigenetics refers to how our inherited genes are used. Behavioral and lifestyle choices affect which genes are switched on, or “expressed”, and which genes are switched off. (Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B. (2014). EPIGENOME A genome “marker” is the epigenomic compound that attached to (our) DNA with instructions, we inherited this as it was passed down generationally, (https://www.genome.gov/27532724/epigenomicsfact-sheet/). While “genome” refers to the whole DNA sequence, the “epigenome” refers to the entire pattern of epigenetic modifications across all genes, including methylation DNA tags. “The epigenome is a multitude of chemical compounds that can tell the genome what to do. The human genome is the complete assembly of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid)-about 3 billion base pairs - that makes each individual unique. ... Rather, they change the way cells use the DNA's instructions”, which means they can be influenced to either turn on or off. EXERCISE AFFECTS EPIGENOME Exercise can be considered a preventative medicine. It can reduce the risk of developing a chronic illness and enhance one's overall well-being. Scientific research has identified some molecular pathways that show how physical exercise produces changes in the human epigenome. This finding indicates the potential for cognitive enhancement, improved psychological health, better muscular fitness, and extends to overall better aging and improved quality of life throughout one's lifespan. “Exercise is a key factor in maintaining our functional autonomy and can protect us from sarcopenic loss of muscle mass and strength which occurs with increasing age, and which is a major contributor to the frailty syndrome, Walston 2012; Cruz-Jentoft et al. 2010; Morley et al. 2001”, (Rea, I. M., 2017). Exercise activates certain genes by adding tags to DNA via methylation. These tags turn on or off gene switches. A regular exercise routine can cause a “modification in the genome-wide methylation pattern of DNA…”. Even a single exercise event causes immediate changes in the methylation pattern of certain genes in our DNA, and thus affects gene expression, (Rea, I. M., 2017). EXERCISE- EPIGENOME-EPIGENETICS Making healthy lifestyle choices like regular exercise is a way each person can actively modify their epigenome, and thus their epigenetics, in an effort to preserve and prolong their lifespan. Exercise activates epigenetic tags added to our DNA, such as methylation, which allows our DNA to better regulate metabolism and create beneficial changes to the skeletal muscle. “The health benefits of physical exercise, especially on a long term and strenuous basis, has a positive effect on epigenetic mechanisms and ultimately may reduce incidence and severity of disease, Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2012”, Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B. (2014). Exercise activates a cellular stress response. Aerobic and anaerobic exercise re-energizes the mitochondria. Our muscle growth during a lifespan is regulated by anabolic, the chemical reactions that synthesize molecules in metabolism, and catabolic, the destructive metabolism and breaking down of more complex substances with the release of energy, mechanisms of our gene expressions. Exercise revitalizes the mitochondrial function in our muscles. “It not only improves muscle function but also quality of life, with exercise improving mitochondrial function in older individuals as much as in younger exercising individuals, Carter et al. 2015; Kang and Ji 2013; Joseph et al. 2012”, (Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B. (2014). While the research referenced in this article focuses on exercise as the influence of epigenetics, the concept can be applied to many other activities like learning new things, exposure to novel challenges and engaging in new tasks. Additionally, these research includes epigenetics in response to addiction and unhealthy lifestyle activities. I've chosen to focus my article on exercise and healthy lifestyle benefits. Express your gene's wisely! References

The neuroscientific underpinnings of embodying the wave of enthusiasm among sport team members, watching a strong team effort, belief in strength-in-numbers and a felt sense of collective winning.

Watching a great sports team perform elicits our mirror neurons and activates embodied simulation. A team’s collective positive energy and group “juju” provides an emotional contagion that can be felt. Oxytocin is a hypothalamic hormone stored in the posterior pituitary at the base of the brain. Oxytocin is directly related to the biopsychological process of developing emotions between people that this extends to sports team members. Integral to a sports team is building trust, cohesion, cooperation, and social motivation among the players. Embodied Simulation Observing or participating is sport team activities creates a shared intersubjective experience, a way to identify socially. Vittorio Gallese, M.D., of University of Parma, states that “Social identification incorporates the domains of action, sensations, affect, and emotions and is underpinned by the activation of shared neural circuits”. He describes the function of these neural mechanisms involved as “embodied simulation”. This mechanism “mediates our capacity to share the meaning of actions, intentions, feelings, and emotions with others”. This shared meaning creates a connectedness to others. A feeling of “we-ness”, p. 520. Observing a team whose belief is strength-in-numbers allows us to embody this belief. We feel a part of them, we identify socially with this idea. It becomes a shared experience. Mirror Neurons Mirror neurons are activated when we observe an action being performed by someone else. When we watch a team sports event, our mirror neurons allow us to mirror their performance and to understand the actions being performed. “Watching someone grasping a cup of coffee, biting an apple, or kicking a football activates the same neurons of our brain that would fire if we were doing the same”, p. 522.Gellese states that “…mirror neurons by mapping observed, implied, or heard goal-directed motor acts on their motor neural substrate in the observer’s motor system allow a direct form of action understanding, through a mechanism of embodied simulation (Gallese, 2005 a,b, 2006; Gallese et al., 2009)”, p. 521. Mirror neurons also allow us to understand the emotions of others. “When we perceive others expressing a given basic emotion such as disgust, the same brain areas are activated as when we subjectively experience the same emotion…”, p. 523. When we observe a team pull together in the face of obstacles, we can imagine ourselves performing the same way, we mirror these actions. “The mirroring mechanism for actions in humans is somatotopically organized; the same regions within premotor and posterior parietal cortices normally active when we execute mouth-, hand-, and foot-related acts are also activated when we observe the same motor acts executed by others (Buccinoetal.,2001). Watching someone grasping a cup of coffee, biting an apple, or kicking a football activates the same neurons of our brain that would fire if we were doing the same”, p. 522. Emotional Contagion Feeling inspired watching a team collaborate and generate a collective winning attitude creates an emotional contagion. This felt sense impacts all members of a group, either positively or negatively. Researcher’s Dezecache, Conty, Chadwick, Philip, Soussignan, Sperber, & Grèzes (2013) examined emotional contagions within a group. Emotional states are spread throughout people spontaneously! People are inherently perceptive of what other’s emotional expressions produce. In their research Dezecache, Conty, Chadwick, Philip, Soussignan, Sperber, & Grèzes (2013) demonstrate that emotions like joy and fear are instantly transmitted throughout a group setting. They show that people are neurologically programmed to respond and react to the emotional signals of others, which in turn produces emotional states. This hard-wired function is a survival mechanism. When we see our team members smile and engage with confidence, we instantly match them. When we see out team members struggle to overcome an obstacle, we struggle with them. Oxytocin Sports team members share experiences and emotions, creating a group cohesion and collaborative effort with a common goal. Research findings illuminate a positive correlation between players who engage in encouraging and supportive behaviors with greater performance and achievements. Their research indicates that “positive social interactions” and “prosocial celebratory behaviors” are linked to the bonding experience of Oxytocin. Expressions of social emotions communicate cooperation and strategies among sports team members. Research also shows that positive emotions “have profound influences on a number of processes, including attentional control, cognition, and interpersonal functioning “. The beneficial subcomponents of sharing positive emotions are linked to performance, perception, attention, memory, decision-making and judgment. “The expression of an emotional state in one person leads to the experience of similar emotions in a person observing the expression…emotions influence other's people's emotions, feelings, and behaviors, leading to the convergence of emotions and moods”, (Pepping & Timmermans, 2012, p. 2). These findings give support to the importance of all team members and how well they interact. “Oxytocin has effects on cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, mind reading, positive and negative social emotion’s…cause convergence of positive emotions and moods between people and make it possible that athletes can respond to the emotional behavior from their fellow players and opponents”, (Pepping & Timmermans, 2012, p. 16). References Dezecache, G., Conty, L., Chadwick, M., Philip, L., Soussignan, R., Sperber, D., & Grèzes, J. (2013). Evidence for unintentional emotional contagion beyond dyads. PloS one. Volume 8:6, e67371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067371. Gallese, V. (2009). Mirror neurons, embodied simulation, and the neural basis of social identification. Psychoanalytic Dialogues. Volume 19(5), pp: 519-536. DOI: 10.1080/10481880903231910. Pepping, G. & Timmermans, E. (2012). Oxytocin and the Biopsychology of Performance in Team Sports. Scientific World Journal. Volume 2012; 2012: 567363. Doi: 10.1100/2012/567363. PMCID: PMC3444846. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22997498. Psychology of Flow States and #OptimalExperiences #PositivePsychology #ConsultingPsychology #Flow4/6/2016 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's research shows that happiness and feeling the flow state of optimal experience isn’t something that just happens. It’s not random or just “luck”. It’s not passive. It’s an active pursuit.

This desired state is not outside of ourselves, it occurs from within, in how we interpret events, our perceptions, and what we do to create circumstances for optimal experiences. It’s something that we work towards, prepare for and learn to cultivate. Once this discipline is harnessed, we become more aware of information and opportunities that are congruent with our goals and desires. Energy flows more easily. Each time we achieve an optimal experience, a positive feedback loop is created and it can be more frequent. “The positive feedback strengthens the self, and more attention is freed to deal with the outer and inner environment” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 39). The quality of one’s life inevitably improves. “People who learn to control inner experience will be able to determine the quality of their lives, which is as close as any of us can come to being happy” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 2). To overcome external experiences that can produce anxieties and depressions, a person must develop the ability to find enjoyment, meaning and purpose regardless of external circumstances. “…It requires a discipline and perseverance that are relatively rare…achieving control over experience requires a drastic change in attitude about what is important and what is not” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 16). Actively participating in creating a flow of optimal experience will create a sense of personal power and an ability to enjoy ongoing experiences. We actively construct how we invest our energy. We can’t consciously reach for a state of happiness. Rather it has to be a by-product of the many details of how we are living and what we are giving our attention to. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) cited Viktor Frankl’s definition from his book Man’s Search for Meaning: “Don’t aim at success-the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued: it must ensue…as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a course great than oneself” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 2). It happens when your busy doing life. Working towards this inner (optimal) experience requires acceptance of situations and experiences that are beyond our control. Once we chose acceptance, we begin from there. We can choose to use our unique abilities and traits to create an environment that works for us. Happiness and optimal experiences are not a passive act. “The bests moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. Optimal experience is thus something that we make happen” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 3). (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 3). Creating ongoing optimal experiences doesn't start out as a pleasant experience. Getting control of our inner experience and perceptions doesn’t come easily. It requires a consistent effort, an active participation in spending time perfecting a craft, tediously working towards a mindset, goal or activity. “…Optimal experience depends on the ability to control what happens in consciousness moment by moment, each person has to achieve it on the basis of his own personal efforts and creativity” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 5). It requires leading a vigorous life, pursuing a variety of interests and continuous learning and striving. It’s about learning to enjoy the journey. References Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: HarperPerennial. Long-term mild exercise improves (spatial) memory and improves the efficiency of cell function.

Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis AHN explained: The hippocampus is significant in the formation of (new) long-term memories and special navigation. Aspects of memory are enhanced with long-term mild exercise (ME). “Exercise increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN)…that is a continuous production of new neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus…and furthermore, exercise-enhanced AHN is considered an important cellular substrate for the development of hippocampal function”, (Graves, A. R., Moore, S. J., Bloss, E. B., Mensh, B. D., Kath, W. L., & Spruston, N., 2012). Neurogenesis in the hippocampus is the growth and development of new pyramidal neurons (cells).The process of neurogenesis is experience-dependent. It’s instigated by new learning and experiences, also referred to as experience-dependent plasticity (neuroplasticity). The experience of long-term running promotes neurogenesis. The BDNF up-regulation following the exercise enhances the AHN. “The hippocampus is the cradle of cognition—a brain structure critically involved in the formation, organization, and retrieval of new memories. The principal cell type in this region is the excitatory pyramidal neuron…” (Graves, A. R., et. al., 2012). Researchers Inoue, K., Okamoto, M., Shibato, J., Lee, M. C., Matsui, T., Rakwal, R., & Soya, H. (2015) discovered that “…treadmill running training with minimizing running stress is effective in enhancing AHN…”, p. 19. Additionally, “…ME improves spatial memory without the influence of the exercise stress that accompanies IE”, p. 11. Changes in the Transcriptome Cells: Exercise-induced DNA changes occur in the hippocampus. Specifically, the DNA analysis showed that ME altered these AHN regulators: lipid metabolism, protein synthesis and inflammatory response. ME significantly enhanced cell survival and neuronal maturation (Inoue, K., et. al., 2015), References Bruel-Jungerman, E., Rampon, C., & Laroche, S. (2007). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity and memory: facts and hypotheses. Reviews in the Neurosciences. Volume 18;2, pp: 93-114. Graves, A. R., Moore, S. J., Bloss, E. B., Mensh, B. D., Kath, W. L., & Spruston, N. (2012). Hippocampal pyramidal neurons comprise two distinct cell types that are countermodulated by metabotropic receptors. Neuron, 76(4), 776–789. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.036 Inoue, K., Okamoto, M., Shibato, J., Lee, M. C., Matsui, T., Rakwal, R., & Soya, H. (2015). Long-term mild, rather than intense, exercise enhances adult hippocampal neurogenesis and greatly changes the transcriptomic profile of the hippocampus. PloS one. Volume 10;6, e0128720, pp: 1-25. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128720. A single session of exercise effects the neural connectivity of a person.

We know from previous research that regular ongoing exercise promotes structural brain changes. Changes that may reverse the declining effects of aging and improve cognitive functioning, among other benefits. Researchers Rajab, Crane, Middleton, Robertson, Hampson & MacIntosh (2014) examined the single session exercise neural connectivity effect that, over time, can accumulate to have a long-term impact. Their study was conducted using a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) as a neuroimaging marker to show brain changes with single session exercise. Single session aerobic exercise showed increased co-activation, after exercise, in the central and parietal lobes (operculum cortices), a region involved in somatosensory motor function and tactile sensation from lower limbs. Also observed was an effect in the basal ganglia region and the thalamus, which is involved in the motor learning and reward process of exercise. References Rajab, A. S., Crane, D. E., Middleton, L. E., Robertson, A. D., Hampson, M., & MacIntosh, B. J. (2014). A single session of exercise increases connectivity in sensorimotor-related brain networks: a resting-state fMRI study in young healthy adults. Frontiers in human neuroscience. Volume 8(625), pp: 1-9. Doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00625. The hippocampus of runners is fine-tuned. Runners produce new neurons which can enhance cognition under low-stress conditions and reduce anxiety under high-stress conditions.

Runner's brains produce the stimulation of new neurons that release GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid) which acts as a neural inhibitory activity which reduces anxiety. This process produces a calming sense in the brain and body. The hippocampus of runners produces a different response to stress as opposed to sedentary people. For runners, physical exertion stimulates neurogenesis (new cell production) in the dentate gyrus, an area in the hippocampus region known for high rates of neurogenesis and receiving excitatory input from the frontal cortex. It also increases production of GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid), which calms the nervous system. Research results support the anti-anxiety effects of long-term running and increased neurogenesis throughout the dentate gyrus (Schoenfeld, T., Rada, P., Pieruzzini, P., Hsueh, B., & Gould, E., 2013). Running generate new neurons (neurogenesis) in the dentate gyrus, an area of the brain responsible for new memory formation, plays a role in stress and depression and decreases anxiety-like sensations. Schoenfeld, T., Rada, P., Pieruzzini, P., Hsueh, B., & Gould, E. (2013). Journal of Neuroscience, 2013 May 1;33(18):7770-7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5352-12.2013. © Lisa Lukianoff 2014 copyright

By: Dr. Lukianoff

Although quantifiable (scientific) results on this topic are still in its infancy, research findings suggest a positive outcome in working clinically with the principles of neuroplasticity for interventions and treatment outcome. Experience-dependent clinical interventions based on the principles of neuroplasticity require a multimodal treatment approach. Implementing the Hebbian principles, a neuroscience theory explaining the process of neurogenesis during learning, with cognitive behavioral techniques, achieving tasks and goals, socializing and exercising, can produce a measurable outcome. “A key principle in neuroplasticity is the value of coupling a plasticity-promoting intervention with behavioral reinforcement…” (Cramer, Sur, Dobkin, O'Brien, Sanger, Trojanowski, & Vinogradov, p. 1598, 2011). Neuroplasticity occurs when the nervous system responds to experiences, thus experience-dependent. Experiences create a stimulus that ignites neural firing patterns in the brain to imprint or re-transcribe an experience, or to reorganize the infrastructure of previous experiences via new neural pathways. Researchers Cramer, Sur, Dobkin, O'Brien, Sanger, Trojanowski, & Vinogradov (2011) examine the function of neuroplasticity in the context of clinical psychology via interventions and treatments, including CNS trauma recovery. “To advance the translation of Neuroplasticity research towards clinical applications, the National Institutes of Health Blueprint for Neuroscience Research sponsored a workshop in 2009. Basic and clinical researchers in disciplines from central nervous system injury/stroke, mental/addictive disorders, pediatric/developmental disorders and neurodegenerative/ aging identified cardinal examples of Neuroplasticity, underlying mechanisms, therapeutic implications and common denominators”, (p. 1592, 2011). Implicit in the clinical application of working with the principles of neuroplasticity is a multidisciplinary and multimodal approach to treatment/interventions. Within the clinical context, the emphasis is on adaptive plasticity, associated with a positive gain in treatment or functionality. Participating in regular physical exercise and learning something new illuminate the experience-dependent neural growth aspect of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis. “Aerobic exercise is associated with increased neurogenesis and angiogenesis…”, “…aerobic exercise programs lasting even just a few months significantly benefit cognitive functioning…have been shown to increase brain volume in a variety of regions (Colcombe et al., 2006; Pajonk et al., 2010)…and to enhance brain network functioning…” (p. 1600, 2011). Exercise enhances cognitive functioning which increases our learning capacity. Interventions and treatments designed with the intention of working with the principles of neuroplasticity are used for various CNS injuries, like traumatic brain injury. These treatment interventions are measurable in terms of outcome. “Interestingly, after spinal cord injury, treatment-induced brain plasticity can be measured in the absence of behavioral change”, (p. 1594). The mechanisms of neuroplasticity apply to a range of CNS injuries and treatments. “Studies of motor recovery after stroke illustrate the principle that many forms of neuroplasticity can be ongoing in parallel. Injury to a region of the motor network can result in spontaneous intra-hemispheric changes, such as in representational maps, e.g. the hand area can shift dorsally to invade the shoulder region (Nudo et al., 1996; Muellbacher et al., 2002) or face region (Weiller et al., 1993; Cramer and Crafton, 2006)”, , (Sur, Dobkin, O'Brien, Sanger, Trojanowski, & Vinogradov, p. 1592-3, 2011). A clinical psychology perspective includes, among many interdisciplinary approaches, a combination of psychopharmacological interventions with cognitive behavioral treatments, and an understanding of the mechanisms involved in the formation of new neural networks, patterns, and pathways. Already established clinical psychological practices closely related to neuroplasticity include developmental psychology and critical periods of (neural) growth. A rehabilitative perspective includes patients who’ve suffered CNS injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury. In particular, patients recovering from stroke are dependent upon new neural growth, neurogenesis, and new neural patterns and pathways, neuroplasticity. The brain of a recovering stroke victim begins reorganizing itself. References Cramer, S. C., Sur, M., Dobkin, B. H., O'Brien, C., Sanger, T. D., Trojanowski, J. Q. & Vinogradov, S. (2011). Harnessing neuroplasticity for clinical applications. Brain, a Journal of Neurology. Volume 134(6); p.p.: 1591-1609. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr039 . Psychological interventions for chronic pain management from a biopsychological perspective requires an integrative and interdisciplinary approach.

Clinically speaking, the experience of an individual’s level of pain incorporates their physiological state, thought patterns, emotions, behaviors, and sociocultural construct. Researchers Roditi, D. & Robinson, M. (2011) state that “…psychological interventions empower and enable patients to become active participants in the management of their illness and instill valuable skills that patients can employ throughout their lives.” In their research findings Roditi, D. & Robinson, M. (2011) identified multiple influences that impact how a person experiences their chronic pain. They point out that it’s both personal and subjective. Keeping a focus on the subjective experience is paramount for treatment approaches. Working clinically with psychological interventions involves focusing on behavioral and cognitive modifications. This includes interventions designed to increase self-management, improve pain-coping strategies, reduce pain-related disability, and reduce emotional distress. It is not appropriate to works towards eliminating the pain source. “…the skills learned through psychological interventions empower and enable patients to become active participants in the management of their illness and instill valuable skills that patients can employ throughout their lives”, (Roditi & Robinson, 2011). The National Institute of Nursing Research reports that pain affects more Americans than diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined. People who suffer from chronic pain are the most common prescribers of medication. Recently the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations required that pain is evaluated as a 5th vital sign. “The IASP’s definition highlights the multidimensional and subjective nature of pain, a complex experience that is unique to each individual”, (Roditi & Robinson, 2011). Part of the complexities of chronic pain comes from the physiological issues that accompany it, the functionality impact it has on a person’s mobility, and the extended period of time that it continues. Behavioral treatment approaches include:

References Roditi, D., & Robinson, M. (2011). The role of psychological interventions in the management of patients with chronic pain. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. Volume 4: pp. 41-49. Doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S15375. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22114534 By: Lisa Lukianoff, Psy.D.

Running and exercise are shown to boost neurogenesis, new cell growth, in adult’s hippocampus region, a region in the brain that promotes regulation of emotion, memory function, and the autonomic nervous system. Researchers Yau, Gil-Mohapel, Christie, & So (2014) examine this process as a potential preventative strategy and treatment to reduce cognitive decline. The structural plasticity of the hippocampal region is altered by neurodegenerative diseases, thus causing cognitive impairment. Exercise and the process of neurogenesis in this region improve cognitive functions. “…hippocampal neuronal circuits known to be involved in spatial learning and possess particular physiological properties that make them more susceptible to behavioral-dependent synaptic plasticity…it is reasonable to speculate that these new neurons might be integral for hippocampal-dependent learning…”, (Yau, Gil-Mohapel, Christie, & So, 2014). Running and exercise have shown a positive correlation between hippocampal-dependent cognitive performance and change in the cerebral blood volume. The results of this research indicate that adults produce new neurons, neurogenesis, in the hippocampus region and this play a vital role in cognitive function, learning, and memory. “…a meta-analysis study has shown that 1 to 12 months of exercise in healthy adults brings behavioral benefits…significant increases in memory, attention, processing speed, and executive function…regular engagement in physical exercise in midlife is associated with reduced risks of developing dementia later on in life…physical exercise might indeed have preventative effects with regard to the development of age-related cognitive decline”, (Yau, Gil-Mohapel, Christie, & So, 2014). Providing a person with a therapeutic prescription of running and/or exercise can be scientifically valid and clinically relevant for working towards restoring and improving the endogenous neurogenic capacity of an individual. References Yau, S. Y., Gil-Mohapel, J., Christie, B. R., & So, K. F. (2014). Physical Exercise-Induced Adult Neurogenesis: A Good Strategy to Prevent Cognitive Decline in Neurodegenerative Diseases?. BioMed research international. Volume 403120; pp. 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/403120 By: Lisa Lukianoff, Psy.D.

Endurance running or just long distance running produces endogenous neurotransmitters called “endocannabinoids” (eCBs). Interestingly this neuroscience term bares a striking resemblance to the function of cannabis. And based on this research, it's nature’s way of providing a calming sense of well-being and reinforcing the rewards of endurance running, neurobiologically speaking. The brain produces its own medicinal properties as a result of endurance activities. We refer to this as "runners high". The eCB neurotransmitters activate the cannabinoid receptors in the reward region of the brain and are activity-dependent. This neurobiological reward system and feedback loop provide a plausible explanation for why humans engage in endurance exercise despite the potential for injury and loss of energy. Endocannabinoid is neuroscience behind the popular reference to a “runners high”. An increase of eCB’s neurotransmitters into the bloodstream enhances a person’s sense of well-being, reduces anxiety (anxiolytic), which produces a calming sense post-run, and also buffers the sensation of pain. “Exercise-induced reductions in pain sensation lead to feelings of effortlessness associated with the strict definition of the runner’s high and improve exercise performance by allowing individuals to run longer distances (Dietrich and McDaniel, 2004). Both the psychological and analgesic effects of CB receptor activation mirror athletes’ descriptions of the neurobiological rewards associated with exercise (Dietrich and McDaniel, 2004)”, (Raichlen, Foster, Gerdeman, Seillier, & Giuffrida, 2012). The release of eCB’s is intensity-dependent, which is why endurance running and other aerobic exercise create enough intensity for this neurobiological reward to function. References Raichlen, D. A., Foster, A. D., Gerdeman, G. L., Seillier, A., & Giuffrida, A. (2012). Wired to run: exercise-induced endocannabinoid signaling in humans and cursorial mammals with implications for the ‘runner’s high’. The Journal of experimental biology. Volume 215(8); pp. 1331-1336. http://jeb.biologists.org/content/215/8/1331.short By: Lisa Lukianoff, Psy.D.

Discoveries in science promote advancements in fields of study. Case-in-point the psychological sciences field is inextricably linked with discoveries in neuroscience. Neuropsychoanalysis, the clinical practice, and study of neuroscience and psychoanalysis, is an emerging field propelling research in the neuropsychoanalytic study of psychological states from a brain science perspective. To study the neural patterns of psychodynamic conflict, scientists Kehyayan, Best, Schmeing, Axmacher, & Kessler (2013) used fMRI scans to measure internal states. The scans revealed psychodynamic conflict in the anterior cingulate cortex and in the emotion-processing regions of the brain. The concept of “neuropsychoanalysis” joins together psychoanalysis and neuroscience to allow for psychoanalytically informed neuroscience. “…if a theme comprised in the subject’s conflict is touched in a real-life situation, reactions on the behavioral, cognitive, and physiological level should be expected, that call for the regulation of cognitions, impulses and, most importantly, emotions”, (2013). Scientists Panksepp & Solms (2012) state that the study and idea of neuropsychoanalysis, which began in the 1990’s, arose from a clinical need to reconcile psychoanalytic and neuroscientific perspectives on emerging discoveries. The overarching goal was to better understand the neurobiological origins of emotions and psychiatric dysfunction. The focus is on brain functions, “Neuropsychoanalysis is especially interested in brain functions that govern instinctual life, in particular, those that are foundational for understanding subjectivity, agency, and intentionality”, (p. 1, 2012). Ideally, the synthesis of these fields will produce a greater understanding of the neurological brain affective networks involved in psychological states and an understanding of higher cognitive functions. “Researchers in this field assimilate the best conceptual tools and clinical observations from the pre-neuroscientific era that sought to understand the complexities of human mentation in their own right, and encourage their integrated use with all the new and old neuroscience techniques needed for a fuller understanding of mind than academic psychology and neuroscience has yet achieved”, (Panksepp & Solms, p. 3, 2012). Based on these findings psychodynamic conflicts viewed by corresponding fMRI studies provide an investigative technique to analyze conflict processing with neuroimaging. References Kehyayan, A., Best, K., Schmeing, J. B., Axmacher, N., & Kessler, H. (2013). Neural activity during free association to conflict–related sentences. Frontiers in human neuroscience. Volume 7(705). Doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00705. http://journal.frontiersin.org/Journal/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00705/abstract Panksepp, J. & Solms, M. (2012). What is neuropsychoanalysis? Clinically relevant studies of the minded brain. Trends in cognitive sciences. Volume 16(1): pp. 6-8. Doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.005. http://www.frontiersin.org/publications/22153583 The process of psychotherapy and re-transcribing past traumatic events invoke our procedural memory, making them explicit and conscious. This process allows for re-transcription of these implicit memories: synthesis realization and integration. A supple brain, elasticity in the brain and the possibilities and limitations of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, in the context of psychotherapy are examined.

How can clinicians implement neuroscience findings in a way that benefits clients? This brief overview highlights some aspects of neuroplasticity, illuminating the significance of working clinically with the plasticity potential of a brain. Key neuroscientific discoveries Our brains are capable of neurogenesis, growing new neurons, and neuroplasticity, creating new neural connections and pathways. Learning is vital for the process of neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. The hippocampus is a region of more neurogenesis than other regions, a significant departure from previous thought. Early traumatic experiences interfere with the normal growth and development of the hippocampus in the limbic region, an area important for memories and emotional regulation. Psychotherapy is a mechanism used to examine past traumatic events and a process of learning about oneself. Neuroplasticity occurs when the nervous system responds to experiences, thus experience-dependent. Experiences create a stimulus that ignites neural firing patterns in the brain to imprint or re-transcribe an experience, or to reorganize the infrastructure of previous experiences via new neural pathways. This process can occur during psychotherapy. Antidepressants have been discovered to increase neurogenesis in the hippocampus (Malberg, J., Eisch, A., Nestler, E., & Duman, R., 2000). This creates the possibility of healing a previously damaged area which affects behaviors. A combination of psychotherapy and antidepressants can profoundly improve a persons mental state. Novel experiences and life-long learning facilitate both neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. Learning is more important than relying on already established skills and established neural pathways. Our brains grow new neurons and pathways from birth until death. Neuroplasticity converges with psychology Research about neuroplasticity brings scientific evidence to the foreground from a clinical use perspective. This collective research expands the field of neuroscience, of neural patterns and the process of neuroplasticity and neurogenesis. Understanding the principles of neurogenesis and neuroplasticity can positively impact clinical work with clients, on a neuron level. Neurons that fire together, wire together. In his book titled The Brain That Changes Itself Doidge (2007) introduces readers to multi-disciplinary scientists, physicians, psychiatrists and neuroscientist, whose collective research demonstrate the plasticity of the brain and introduces the idea that the brain changes based on new information. Norman Doidge, M.D. (2007) conducted research and interviews with many “neuroplasticians” which firmly coined the phrase neuroplasticity. These advancements in neuroscience inextricably link psychological science with neuroscience. Doidge (2007) cites the research of Eric Kandel, a physician, psychiatrist and 2000 Nobel Prize winner who stated: “there is no longer any doubt that psychotherapy can result in detectable changes in the brain”. Kandel continues to research the hippocampus and the plasticity of implicit and explicit memory. Other citations include that of neuropsychologist Mark Solms and neuroscientist Oliver Turnbull who state that “the aim of the talking cure…from the neurobiological point of view is to extend the functional sphere of influence of the prefrontal lobes”. These discoveries provide evidence of the significance of the intersubjective experience between a clinical practitioner and a client. Giving scientific weight to the function of neuroplasticity in the context of personal exploration in therapy, e.g. a talking cure, psychotherapy, Doidge (2007) discusses the neurological process of analysis. The benefit of a client talking about past traumatic experiences facilitates the unconscious procedural memory to integrate past trauma with a better understanding. This can produce a calming effect from a neurological perspective. "In the process, they plastically re-transcribe these procedural memories, so that they can become conscious explicit memories...” This allows a person to remember without reliving the emotions of painful past experiences. In their research Garland, E. & Howard, M. (2009) provide further support for the neuroplasticity growth in response to learning and therapy. “Investigations of neuroplasticity demonstrate that the adult brain can continue to form novel neural connections and grow new neurons in response to learning or training even into old age”. Novel experiences create these new neural connections throughout the lifespan. Not all of the discoveries lead to enhanced psychological states. While neuroplasticity shows how thoughts and actions can change the brain to create new structures and functions, thus new ways of understanding, we are also introduced to the rigidity of well-established neural networks, also a product of neuroplasticity (Doidge, 2007). Doidge refers to this as the “plastic paradox” whereby the same neuroplasticity that allows our brains to change can also keep us constrained and “stuck” by well-established neural patterns. Debunking previously held thoughts about Localization Mainstream psychological science and medicine held the collective belief that the brain was hard-wired and that cells continued to die off. Localizationist’s we more popular and believed that the neuroanatomical structure of the brain was a machine-like device with specific areas for specific functions. Neuroscience has demonstrated that multiple areas of the brain are involved in similar functions and can also rewire to compensate for a damaged area. The research shows that many areas of the brain can be used for multiple functions. Localization of the brain has been re-defined. Multi-disciplinary Among the neuroscientists Doidge (2007) interviewed was Paul Bach-y-Rita. In 1969 Paul Bach-y-Rita published an article in a European science journal citing his research using a machine that sent signals to the damaged area of a brain that ultimately cured retinal damage in some cases. Bach-y-Rita’s research demonstrated that our brains were capable of neuroplasticity and using other area’s to restructure and create new neural growth. The research publication and its avant-garde nature caused isolation from some of his peers. Bach-y-Rita had a multi-disciplinary background and approach and tended to follow ideas as they evolved. As a neuroscientist, he had expertise in medicine, psychopharmacology, ocular neurophysiology, visual neurophysiology, and bio-medical engineering. Doidge (2007) asserts that Paul Bach-y-Rita stated “we see with our brains” and that if one area is damaged, another area can take over. He referred to this process as “sensory substitution”. Psychotherapy changes the brain It was Eric Kandel who “was the first to show that as we learn, our individual neurons alter their structure and strengthen the synaptic connections between them…” Doidge explained that Kandel’s work demonstrated that learning produces new neurons in the brain that influence our genes and that psychotherapy changes people’s brain structure, “it presumably does so through learning, by producing changes in gene expression that alter the anatomical pattern of interconnections between nerve cells”. Further support of these brain changes, researchers Liggan & Kay (1999) discuss the neural mechanisms of memory in the context of psychotherapy and reveal that the brain does change, “…neural mechanisms of memory is based on discoveries that training or differential experience leads to significant changes in brain neurochemistry, anatomy, and electrophysiology. Consequently, it is generally accepted that psychotherapy is a powerful intervention that directly affects and changes the brain”. Liggan & Kay (1999) also demonstrate how psychotherapy affects cerebral metabolic rates, serotonin metabolism, the thyroid axis, and stimulates processes akin to brain plasticity. References

How do you evaluate clients level of resilience and "stress inoculation"? A client may have better-coping mechanisms & an HPA-axis that regulates hormones more efficiently because they've been through tough times. Has your client handled unexpected stressful events throughout the course of their life and come out the other side a little stronger?

The idea behind the “stress inoculation” effect is based on the hypothesis that exposure to moderate amounts of stress over a prolonged period of time helps an individual develop better-coping mechanisms, better resilience. Potentially. Scientific researchers Russo, Murrough, Han, Charney & Nestler (2012) have studied the adaptive biopsychology of resilience in terms of an active behavioral, neural, molecular, and a hormonal basis. These researchers state that the phenomenon of resilience has remained a mystery, biopsychologically speaking. Yet remarkably a high percentage of people exposed to intense levels of trauma and stress manage to maintain a relatively normal psychological homeostasis, (p. 1). “Within the general population, between 50–60% experience a severe trauma, yet the prevalence of illness is estimated to be only 7.8%. Children in particular display remarkable resilience across a range of negative environmental stressors”, (p. 6). Could this be an example of stress inoculation? Interestingly, "..."Stress resilience is enhanced in specific populations, such as military personnel and rescue workers, through controlled exposure to stress–related stimuli". Here is a population whose primary work exposes them. What biological factors allow for this? To explore the underpinnings of this phenomenon, they examined the role of the neuroendocrine system as the neurobiological coping mechanism. Basically, the neuroendocrine system is the “house” that regulates the hypothalamus and other mechanisms involved in the maintenance of a person’s overall homeostasis. This includes a person’s regulatory systems like metabolism, hunger, energy output and blood pressure levels. Research shows the neurobiology of resilience is mediated by the presence of unique molecular adaptations in the neuroendocrine system: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, production of Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and Testosterone. The HPA axis is the main mediator of the initial impact of stress on the brain. It regulates hormonal, neurochemical, and physiological changes. “Glucocorticoids, released from the adrenal cortex as a consequence of HPA axis activation, interact with steroid receptors expressed throughout the brain that functions primarily as transcription factors to regulate cellular function beyond the time scale of acute stress effects”, (pp. 2-3). This whole process drives the behavioral response a person experiences. However, the exact effect of this relationship between HPA and resilience is unclear. In the same area, Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is released, along with cortisol, in response to stress. Russo, Murrough, Han, Charney & Nestler (2012) propose that current research about DHEA suggests that it counter’s the negative effects by producing an anti-inflammatory response, (p. 1476). “It has been reported that DHEA responses to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) were elevated in PTSD and negatively correlated with the severity of symptoms, suggesting that DHEA release during stress may buffer the severity of PTSD”, (p. 3). Oddly, the hormone DHEA released during stress can actually help alleviate the negative response. Testosterone is released in response to stress is considered to serve as a pro-resilience hormone creating a positive mood and connectedness, and important among sports team members. Interestingly, after the experience of a stress event, testosterone levels decrease for a period of time. "...Early studies in men suggest that testosterone may be effective in treatment–resistant depression and as an adjunct to SSRI treatment..." (p. 3). “it seems clear that moderate degrees of stress exposures during early life, adolescence, and adulthood can shift an individual’s stress…by increasing the range of tolerable stress for the organism”, (p. 7). These early exposures possibly prime the HPA axis to function more efficiently; producing moderate levels of hormones released thus allowing for less impact and more recovery. These findings and further research outcomes can have significant clinical implications for future treatments. "...far more insight is needed into the genetic, epigenetic,neurobiological, and neuroendocrine basis of sex differences in stress susceptibility vs. resilience. Finally, we need to better define how just the right type and level of stress inoculation, through this complex interplay of mechanisms, can promote resilience..." References Russo, S. J., Murrough, J. W., Han, M. H., Charney, D. S., & Nestler, E. J. (2012). Neurobiology of resilience. Nature neuroscience. Volume 15(11); pp. 1475-1484. Doi:10.1038/nn.3234. Found online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3580862/ Link to article: .http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v15/n11/abs/nn.3234.html fMRI studies show neurological changes & activity in patient's receiving psychotherapy treatment. Implicit in these findings are both neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, a byproduct of treatment.

Researchers Buchheim, Labek, Walter & Viviani (2013) designed an empirical research study to investigate the outcome of long-term psychotherapy from a neurobiological perspective. “In the present study, we attempted to integrate a clinical description of the psychoanalytic process with two empirical instruments…brain activity based on a functional neuroimaging probe”, (p. 9). They wanted to create a study that would allow us to “see” the effects of psychotherapy on the brain. To accomplish this, the design included using clinical data, a standardized instrument of the psychotherapeutic process (Psychotherapy process Q-Set, PQS), and functional neuroimaging (fMRI). fMRI scans were administered after therapy sessions while the patient viewed the Adult Attachment Projective Picture System (AAP). This was done for 12-months. In their research findings Buchheim, Viviani, Kessler, Kachele, Cierpka, Roth, George, Kernberg, Bruns, & Taubner (2012) show improvements in depressive symptoms and neural activity in regions of the brain. "This is the first study documenting neurobiological changes in circuits implicated in emotional reactivity and control after long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy". These scans showed neurological changes and activity in both patients receiving psychotherapy treatment. In particular, the fMRI’s scans showed changes in the hippocampus, amygdala , subgenual cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex after psychotherapy treatment. These findings documented neurobiological changes and a reduction of emotional reactivity after long-term psychotherapy. “The significant association of the changes in the subgenual cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex with symptom improvement supported the hypothesis of their relevance to the changes intervened during therapy”, (p. 5). They conducted a single-case study of a 42-year-old woman who received psychotherapy treatments for one year. The patient was described as having a disorganized attachment style with narcissistic traits, characterized by chronic fluctuating moods and self-esteem. The fMRI scans revealed neural activation in the ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This area is associated with controlling one’s focus and attention, and depression. Other neural activation revealed from the fMRI scans included the pregenual portion of the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate and precuneus, the middle temporal gyrus, and the anterior tip of the inferior temporal gyrus, and the occipital calcarine cortex. Buchheim, Labek, Walter & Viviani (2013) felt that these areas were most significant to this study because “The medial prefrontal cortex may also be associated with changes after the therapy of affective disorders…” (p. 9). They believe that observable neurological changes from therapy will be most visible in these brain regions. The neurological response to psychotherapy allowed them to track this patient’s defensive characteristic via neural activity viewed in the scans. “Using functional neuroimaging, we were able to objectify the defensive structure of this patient during this phase of psychoanalytic treatment and the occurrence of difficult sessions”, (p. 11). While these research findings may not answer many important questions, they do show a distinct correlation between psychotherapy treatments and neurological activity. More research is needed in this area. “The relevance of these finding for future studies rests in the possibility of documenting specific mechanisms of action of depression therapy by systematically collating results from different studies and comparing different psychotherapeutic approaches…”, (p. 6). References Buchheim A, Labek K, Walter S, & Viviani R. (2013). A clinical case study of a psychoanalytic psychotherapy monitored with functional neuroimaging. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. Volume 7(677); pp. 1-13. Doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00677. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3805951/ Scientific research that gives weight and meaning to the importance of good group juju!

Essential for athletes on a (sports) team is the ability to understand the intentions and goals of each other and of their opponents. To do this they must be able to communicate accurately, have positive social connections, and convey a strong sense of group cohesion among the team. All of this is needed for a successful performance. This article is a brief overview of the biological psychology process involved in creating a positive mindset among sport team members. It begins with an introduction into the neuroscience behind emotional bonds and how they are relevant. It then expands into a discussion about how positive emotions encourage a better performance overall. These findings are specific to a sports team of players but are also useful among any team group. In their research Pepping & Timmermans (2012) examine the role Oxytocin plays in the biopsychological process of emotions and moods. Oxytocin is a hypothalamic hormone stored in the posterior pituitary at the base of the brain. This hormone is vital in women during childbirth and lactation, in men and women and how they form pair-bonds in intimate relationships, in social memory, social recognition, and social attachment behavior. Since Oxytocin is directly related to the biopsychological process of developing emotions between people, Pepping & Timmermans (2012) assert that this extends to sports team members. Integral to a sports team is building trust, cohesion, cooperation, and social motivation among the players. Sports teams share positive experiences and emotions, creating a group cohesion and collaborative effort with a common goal. Research findings illuminate a positive correlation between players who engage in encouraging and supportive behaviors with greater performance and achievements. Their research indicates that “positive social interactions” and “prosocial celebratory behaviors” are linked to the bonding experience of Oxytocin. Expressions of social emotions communicate cooperation and strategies among sports team members. Research also shows that positive emotions “have profound influences on a number of processes, including attentional control, cognition, and interpersonal functioning “. The beneficial subcomponents of sharing positive emotions are linked to performance, perception, attention, memory, decision-making and judgment. “The expression of an emotional state in one person leads to the experience of similar emotions in a person observing the expression…emotions influence other's people's emotions, feelings, and behaviors, leading to the convergence of emotions and moods”, (Pepping & Timmermans, 2012, p. 2). These findings give support to the importance of all team members and how well they interact. The bonding effects of Oxytocin enhance the ability for empathy. In very general terms empathy is the capacity to see things from another person’s perspective and to recognize the internal (emotional) states of another. What this research shows is that an increase in Oxytocin produces an increase in the capacity for empathy. Empathy is also related to a player’s ability to perceive the opponent's intentions. “Oxytocin has effects on cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, mind reading, positive and negative social emotions…cause convergence of positive emotions and moods between people and make it possible that athletes can respond to the emotional behavior from their fellow players and opponents”, (p. 16). The researcher’s on this team agree that more research is needed on this topic. They believe that new discoveries will have a “significant importance for sport psychological and sports science support, talent identification, coaching, training, team selection, and team development”, (p. 16). References Pepping, G. & Timmermans, E. (2012). Oxytocin and the Biopsychology of Performance in Team Sports. Scientific World Journal. Volume 2012; 2012: 567363. Doi: 10.1100/2012/567363. PMCID: PMC3444846. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22997498 Researcher Dr. Eric Kandel, whose contributions at Columbia University include the molecular basis of memory and a team, discovered therapeutic interventions like exercise help reduce age-related memory loss. “We were astonished that not only did this improve the mice’s performance on the memory tests, but their performance was comparable to that of young mice,” said Dr. Pavlopoulos.“The fact that we were able to reverse age-related memory loss in mice is very encouraging,” said Dr. Kandel.

They examined proteins in human cells in the hippocampus region that contribute to memory functions. These proteins, RbAp48 and the PKA-CREB1-CBP, are valid targets for therapeutic intervention. Agents that enhance this pathway have already been shown to improve age-related hippocampus dysfunction in rodents. “But the broader point is that to develop effective interventions, you first have to find the right target. Now we have a good target... we have a way to screen therapies that might be effective, be they pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, or physical and cognitive exercises.” http://newsroom.cumc.columbia.edu/blog/2013/08/28/a-major-cause-of-age-related-memory-loss-identified/ Organizational cognitive neuroscience (OCN) is a new term used to describe the intersection, integration and application of nueroscientific discoveries with organizational and consulting psychology.

OCN is being defined in business leadership and marketing research. "…taking a wider nueroscientific approach to researching marketing or business-relevant problems and decisions will allow a greater understanding of why in general we behave or react the way we do, and a correspondingly greater ability to predict this”, (Lee, N., Butler, M., & Senior, C., 2010, p. 130). Discoveries in neuroscience have produced scientific technological advances using fMRI brain imaging devices. This brain imaging technology has allowed scientists to map activity within regions of the brain to examine human behaviors and responses. These discoveries are expanding organizational psychology towards more neurobiological based interventions and assessments. We now have a greater understanding and insight into the process of emotional arousal and response patterns for individuals. Brain science imaging techniques are able to teach us and show us the neurological process of decision-making. “By combining this approach with functional brain scanning it is possible to understand which areas of the brain generated that specific emotional response—and whether distinct brain regions are involved in other types of decision making”, (Lee, N., Butler, M., & Senior, C., 2010, p. 130). Organizational cognitive neuroscience (OCN), while still in its infancy, is quickly forging a new way of thinking about human behavior and decision making from a neurobiological brain systems approach. References Lee, N., Butler, M., & Senior, C. (2010). The brain in business: neuromarketing and organizational cognitive neuroscience. Journal of Marketing. Volume 49; pp. 129–131. doi: 10.1007/s12642-010-0033-8.http://cms.springerprofessional.de/journals/JOU=12642/VOL=2010.49/ISU=3-4/ART=33/BodyRef/PDF/12642_2010_Article_33.pdf |

AuthorThis blog is intended to explore ideas, educate, entertain and expand our thinking. Some posts speak to current trends in the brain sciences, neural benefits of exercise & sports, emotional intelligence and personal growth. Categories

All

Archives

October 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed